RON GILBERT—Interview by John Skylar and 8bits Considered

Ron Gilbert is a game designer who built the “Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion,” or SCUMM engine, which was used for countless adventure games, both from Humongous Entertainment and LucasArts. He is perhaps best known for designing the cult classic The Secret of Monkey Island. Mr. Gilbert now blogs about gaming at Grumpy Gamer, his personal site.

Night Dive: Most gamers know who you are. You influenced almost every LucasArts adventure game. People call you a “legend.” Your “Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion,” or SCUMM engine, ended up being used in all of those games. How did it feel at the time you were doing these things, like making the SCUMM engine?

Ron Gilbert: I think most people assume that when Gary [Winnick] and I were working on Maniac Mansion, which started the whole point and click genre, that we had some grand vision for this thing and we knew we were creating something important. At the time, we were just trying not to get fired. I think neither of us had any sense of what we were creating. It was the same thing forMonkey Island. It was just a weird idea I had about a pirate, and I just started to make a game about it.

ND: But Monkey Island was such a hit!

RG: You know, I left Lucasfilm after Monkey Island one and two to start Humongous Entertainment, and people are often surprised that I left. People often think that the Monkey Island games were huge hits, so why would I leave? They weren’t huge hits. They sold well, but Sierra Online and King’s Quest were still kicking our ass completely! I was super proud of the games, and I really loved them and all that, but it’s not like it was some monster franchise. It wasn’t until five or ten years later that they got this cult status. At the time when I was at Lucasfilm, I was just making games that I thought were fun. I didn’t have any grand sense of what was going on with them.

ND: That’s kind of what I expected. I feel like it’s the things that we never expect that…kind of trivially…come around and surprise us.

RG: I think that people who think they’re doing something important, probably aren’t. The truly important things that we do, they come by surprise.

ND: You mentioned that you left LucasArts [Lucasfilm Games at the time] after making the Monkey Island games. When you founded Humongous Entertainment, you brought the SCUMM engine with you. Did that require any special arrangement?

RG: Yeah, the SCUMM engine was owned by Lucasfilm. There were three people there who had worked on it. There was Aric Willmunder, Brad Taylor, and myself. When I left to start Humongous Entertainment, I took Brad Taylor with me, which only left Aric Willmunder at Lucasfilm. The deal that I arranged with them is that I could continue to use and work on the SCUMM engine, but any changes I made would flow back to Lucasfilm. I would continue to work with Aric developing the SCUMM system for both companies, and in exchange I got a license to continue using the engine.

ND: That’s a great deal, actually. It’s amazing the kind of good business sense that LucasArts has showed in gaming.

RG: Right.

ND: Speaking of leaving LucasArts, when you were there, you worked more on “all ages” games. Why did you switch to making games for younger gamers when you founded Humongous Entertainment?

RG: I think the word “switch” is a little bit misleading. The whole idea for making the adventure games for kids at Humongous Entertainment came from my watching Shelley Day’s son play Monkey Island. Shelley was a producer at LucasArts, and she cofounded Humongous Entertainment with me. Her son was five at the time, and I saw him playing Monkey Island. He couldn’t really read yet, so he had no idea what was happening—this was before voice, so there was just a bunch of text flashing on the screen. He couldn’t read the verbs, but he figured out that this verb opened the door, and that verb took something…he deduced it all.

ND: Wow, smart kid.

RG: Yeah, and he was fascinated with the game. He would spend hours playing this game but had no idea what was happening in the story. He just loved walking around the world, clicking the “open” verb and watching the doors open. It was just fascinating. He was probably making up this entire story in his head for what was going on, and it got me thinking, “What if I built adventure games specifically for him?” So we turned to making games that were fully voiced—which was totally new at the time, nobody was doing that—so he didn’t really have to read, and where the puzzles were simplified. Not dumbed-down, but just simplified so kids could deal with them. I thought that kids would really like these games, because of the way that he was liking adventure games.

ND: Turns out you were right!

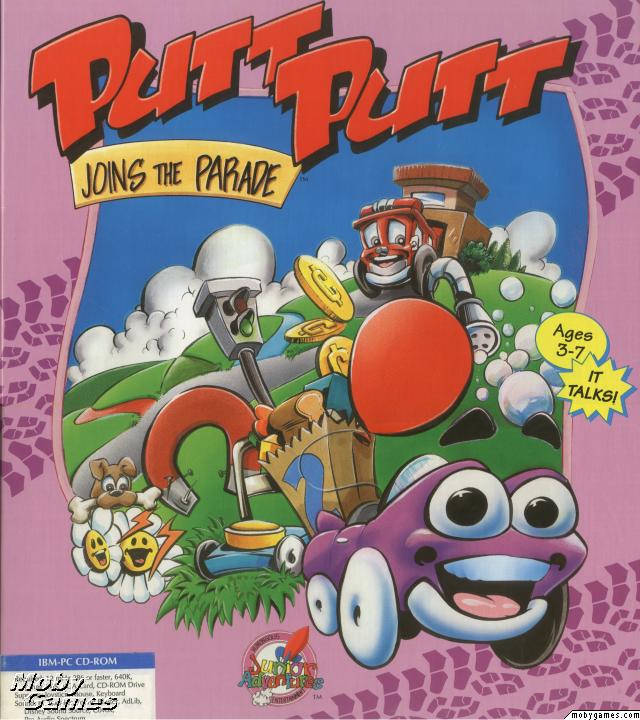

RG: I didn’t just want to build games for kids, lots of people were building games for kids. I wanted to make adventure games for kids, because they’re very story- and character-centric. There’s a lot of puzzle solving going on, but they’re not overtly educational. We didn’t want to teach kids to read or to do math. We wanted to just teach them to solve puzzles and use their brains. And we didn’t just want to build games for kids, but we also wanted to build games that parents would enjoy playing. We didn’t want parents to dread the time that they had to sit down with their kids and play that game. Our model was Disney movies. Parents don’t mind taking their kids to Disney movies, because the movies are told at two levels, one for the kids to enjoy and another level with a sophistication that the parents can enjoy. For the Humongous games, we tried to have that. I think we succeeded, because we got a lot of letters from parents saying as soon as their kids went to bed, they would start up PuttPutt or Freddi Fish or Pajama Sam and they would play it.

ND: Wow!

RG: In a way, the world was different back then. Most parents today were gamers when they were kids, and these parents weren’t, so this was all a new experience for them. The parents were really enjoying these games, where they probably wouldn’t have enjoyed Monkey Island because it relied on a gamer’s knowledge of a game’s complexity. Our games didn’t have that, so these parents could enjoy them too. We always felt that we weren’t designing kids’ games, we were designing games that happened to be for kids. There’s a subtle distinction there, but in the Disney analogy, they’re not making kids’ movies, they’re making movies for kids.

ND: Well, I’ll admit that at the time you got me hooked. I don’t want to scare you, but I was six when you founded Humongous.

RG: [laughs] I run into people who played my games as kids a lot, and yeah, it makes me feel old.

ND: My family didn’t even own a computer, so I used to go over to a neighbor’s house specifically just to help PuttPutt save the zoo for the billionth time. I remember thinking, “Wow, this is so much better than Math Blaster,” because there was a real story.

RG: Yeah, we were really careful not to just make educational games. We always thought of what we were doing as making bedtime stories. In the same way that parents will read their kid stories—they’re not reading their kids math books or books on how to spell. They’re reading their kids nice little stories with morals that the kids can learn something from. We were trying to make that, in games.

ND: Well, that’s really important. So much of keeping people interested is in remembering that storytelling needs to be entertaining.

RG: It was a very conscious decision to name the company Humongous Entertainment rather than Humongous Games, because we wanted to remember to be an entertainment company first, even though we only ever made games.

ND: So that subtle distinction would always be there to remind you to keep it fun?

RG: Right.

ND: In that case, it’s really interesting the variety of ideas that you came up with to keep people entertained, so let me hit you with a few related questions: Why a car? Why a fish? Why a kid in his pajamas?

RG: [laughs] I mean, I don’t know that I can really answer that question. Why a pirate? Why anything? Stuff just pops into your head at some level. Pajama Sam, though, that’s kind of interesting…when I first started to think of him, he was actually called the Pumpkin Head Boy, and he wasn’t necessarily in pajamas. He had nothing to do with Halloween, he just had a pumpkin for a head. And about a month into doing the concepts for that, our head of marketing came to us and he said, “We can’t do the pumpkin head boy game, because everyone will think of it as a seasonal game and it will only sell at Halloween.” And at first, I thought, “That’s stupid, don’t tell me what to do creatively,” but the more I thought about it, the more I realized he was totally right. I could have continued to do it as the pumpkin head boy, but I think it would’ve impacted that game a lot because people would have thought of it as a Halloween game. So we brought the whole team together and started brainstorming different names, and Rafael [Calonzo Jr.], who did the art for it, started cranking out a lot of stuff, and Pajama Sam came out of that.

ND: I guess sometimes you really do need marketing people to remind you that creative stuff still needs to sell, huh?

RG: It’s true, and that was one of the things that was really very influential on me at Humongous Entertainment. I got a lot of exposure to things like sales and marketing, which I had no exposure to at LucasArts. At Humongous, Shelley Day dealt with the business end of things, and I dealt with the creative end of things. It was a good division because I’m not a business guy, but I learned a lot from watching the business people. We hired a VP of marketing and a VP of sales, and I really saw firsthand the amazing influence that these people had on our success. It’s not just that if you make a great game, people will flock to buy it. They won’t, and that’s even true today. If nobody can discover your game, it’s not going to sell. If you have good marketing people who respect the creative process, it’s a wonderful marriage, and we had that.

ND: Given that you hired experts to do marketing and sales, did you hire any child psychology experts to work on the games and their marketing?

RG: We didn’t have, like, child experts who would tell us what kids do or don’t do. What we did was a lot of playtesting where we would bring kids in and watch them play the games. We would pay a lot of attention to the kids and how they were playing the games, and what they were responding to versus what they were having trouble with.

ND: It sounds like, if anything, you really made an effort to become child experts.

RG: Yeah, in a non-institutional education sense. We wanted to understand what it was the kids were liking about the games. Kids played the games in a different way than how adults played Monkey Island. The kids were more interested in just goofing around in the game whereas adults are more interested in solving a game. One of the things Humongous Entertainment had were what we called “clickpoints,” which you would click and they would just do funny animations. They didn’t have anything to do with the puzzles, they were just fun. We added those because kids liked goofing around in the game.

ND: Was there anything else you noticed about the kids’ playing styles?

RG: Yeah, an adult would play Monkey Island once, and they maybe five years later, they’d play it again. Kids would play PuttPutt and then immediately play PuttPutt again, just like they’d watchThe Little Mermaid every afternoon for six months. I don’t know if you have kids, but kids do like the comfort that comes with a familiar story. We decided that we needed to cater to that, to have an environment that the kids can go into and even though they know the story, they’ll enjoy it over and over again.

ND: Oh, yeah. I remember playing the hockey minigame in PuttPutt Saves the Zoo for an entire day once because we thought the voiceovers were hilarious. I think you really “got” what kids are all about. Do you happen to have kids?

RG: No, I don’t, actually.

ND: Well, in a way, you’ve raised an entire generation of kids, so I guess you’ve been pretty busy! With all the different things that you’ve done, do you ever feel like you’re spread too thin?

RG: No, I really like doing new things. I wouldn’t like it if all I made every day were adventure games. Even though I love designing adventure games, I do like doing different things. That’s kind of where Humongous Entertainment came from; I wanted to try new things, to try something different. And so no, I don’t feel spread thin.

ND: That’s great. You’re obviously you’re very creative, and it’s good to hear that in a world where it’s hard to be creative and still pay the bills, you don’t feel that way.

RG: [laughs] Yeah. I feel like I’m just kinda trying different things.

Look for the re-release of 28 Humongous Entertainment games on Steam and [OTHER VENUES], out now!